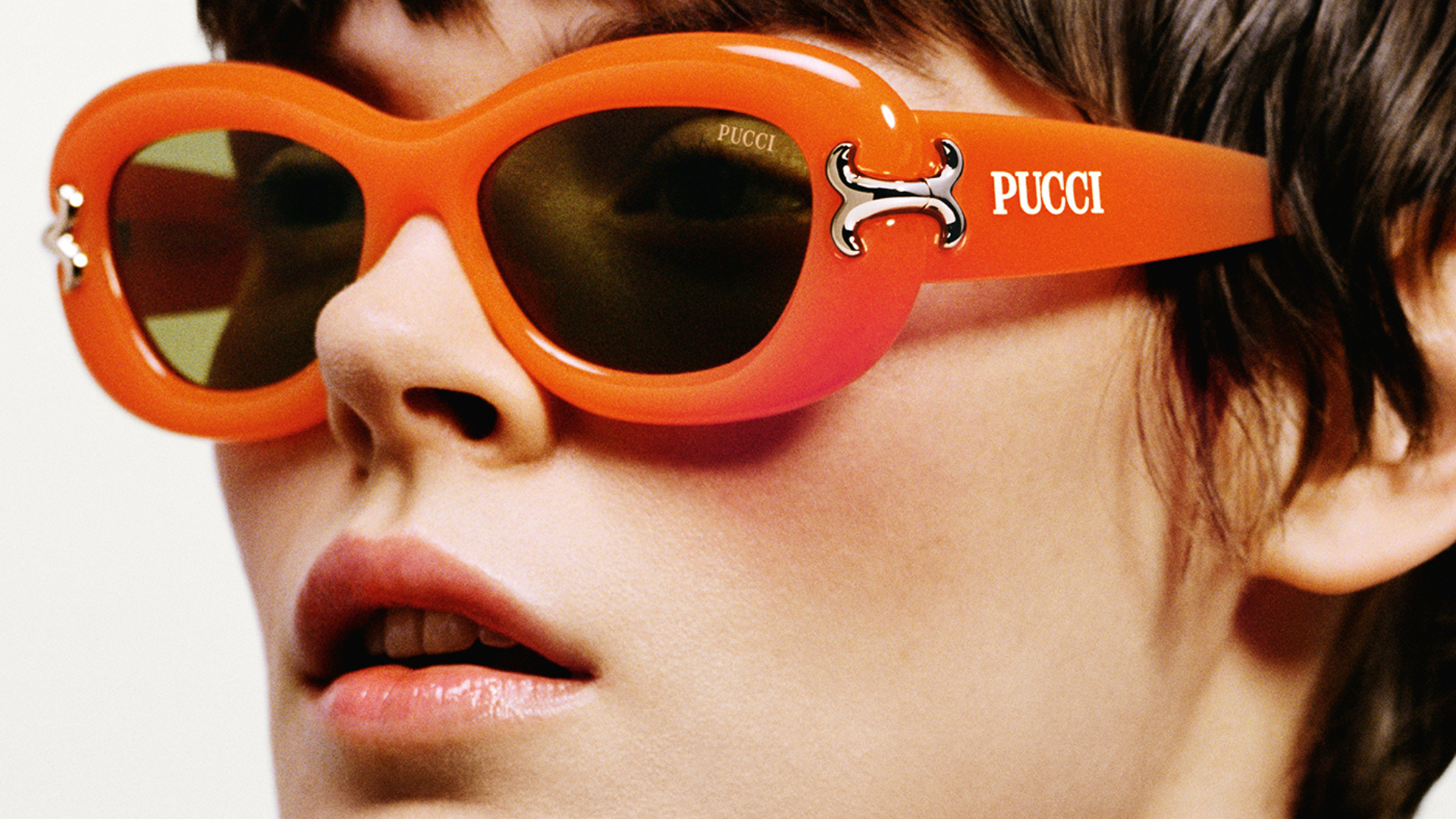

Photo: Courtesy of Pucci Eyewear

Tell me a story

Back to storiesAbout

The eclectic 1970s

The 1970s were all about those major themes that accompanied the tumultuous transition to the contemporary world we know. A transitional era full of contradictions, whose influences on taste have permeated the spaces and objects of our everyday life in various ways. Eyewear included.

Star issues

This is what we could call the themes, like the echoes of the famous (star) wars by director George Lucas, that marked the decade: amidst new intergalactic and imaginary spaces to be explored, political and social revolutions that defined its contours through the renewal of taste and lifestyle of an era that was revolutionary in many ways. This turmoil, which was linked to the revolutions of the previous decade through a contradictory sense of defeat and victory at the same time by those involved in the counterculture, rediscovered an individualism that tended to express itself in eccentricities: from the serial and irreverent art of Andy Warhol to the disturbing sounds of Lou Reed and the Velvet Underground, through to Elton John and David Bowie, who with unparalleled originality sang of the unknown of another space beyond the earth. And in terms of design, how did this turmoil permeate everyday spaces and accessories? Through a revolution of taste with unequivocal intent.

Catalysing what we see

The identity of the decade shifted from the world of ideas to the world of design with a significant post-modern twist. It was the clean, essential lines of the world of objects, particularly those relating to lighting – with the consecration of the immaculate white pendant lamps – that were juxtaposed with imaginative, typically optical effects, the result of influences from the world of psychedelia still in vogue, characterising the geometric shapes of the brightly coloured wallpapers that decorated homes. The destiny of colours seemed tied in with that of shapes artfully constructed to deceive the eye: optical art, which originated at the end of the 1960s, developed and found the best framework to express itself in the decade that followed, combining two colours in particular: black and white, the matching of which gave way to its most congenial use in fashion and accessories. The mood board of this style, with its nods to science fiction, also through the use of oversized glasses with a printed effect, is well captured in the video clip created by Jack Whiteley and Laura Brownhill for the song Bennie and The Jets, by Elton John, who at that time was intent on carving out a place for himself in the temple of style: performing in front of an audience with flashy sunglasses, richly decorated even at sunset, becoming a viaticum for the iconography of an era. But it was the boldly shaped and brightly coloured glasses that best represented the ironic and eagerly light-hearted tones of that current of taste, the offspring of those flowers we all know, which helped give a new impetus to the objects and interior design of the period. The close link claimed by the revival of oriental philosophies and the need for a sense of wellbeing linked to a state of nature is imbued with the trend that still influences Marcolin’s most glamorous and luxury collections, with their bold shapes and pastel colours.

It was the boldly shaped and brightly coloured glasses that best represented the ironic and eagerly light-hearted tones of that current of taste, the offspring of those flowers we all know

Experimenting with new materials

Just like designers of the decade, turning to new shapes and materials. From pop culture and the world of animation came mouths, hands, vegetables to be transformed into the most eclectic of seats. From the desire to experiment, however, came the need to focus on new materials. Even controversial ones. This is not the case with foam rubber – the forerunner of polyurethane foam – but with plastic, regarding the use of which the two opposite poles of the counterculture clashed: the hippy one, which abhorred the very word because “…plastic was used for mass-produced objects, easy to manipulate and lacking in authenticity. Plastic people had the same attributes,” as Ken Goffman wrote in his book Counterculture Through the Ages. In contrast, for Warhol, plastic possessed qualities: flexibility, mutability, variability. “In the realm of authenticity, flexibility can be suspect,” Goffman continued, pointing out the contrast in aesthetics and thinking of a highly contradictory decade, which prompted part of the hippy movement to follow Warhol’s eccentric variability, characterised by his ironic detachment. After all, the artist went down in history for being attracted by money, fame and superficial beauty.